In 1943 I was born into a world at war. My father, an American infantry captain, was in New Guinea with General Robert Eichelberger’s Eighth Army. Eichelberger later disclosed that his marching orders from General MacArthur had been to clear New Guinea of the enemy or not return. Both he and my father survived, but in my father’s case, with hearing loss, battle fatigue, malaria and foot fungus. He managed to shake the malaria.

As he put it so eloquently in one of his few comments about his wartime experiences, they hunkered in tents at night with a blanket of artillery overhead so they could sleep, nothing to fear but a short round or extending lull. Incursions followed lulls. No great wonder he spent the rest of his life in the deafening quiet that signaled an incoming New Guinea nightfall.

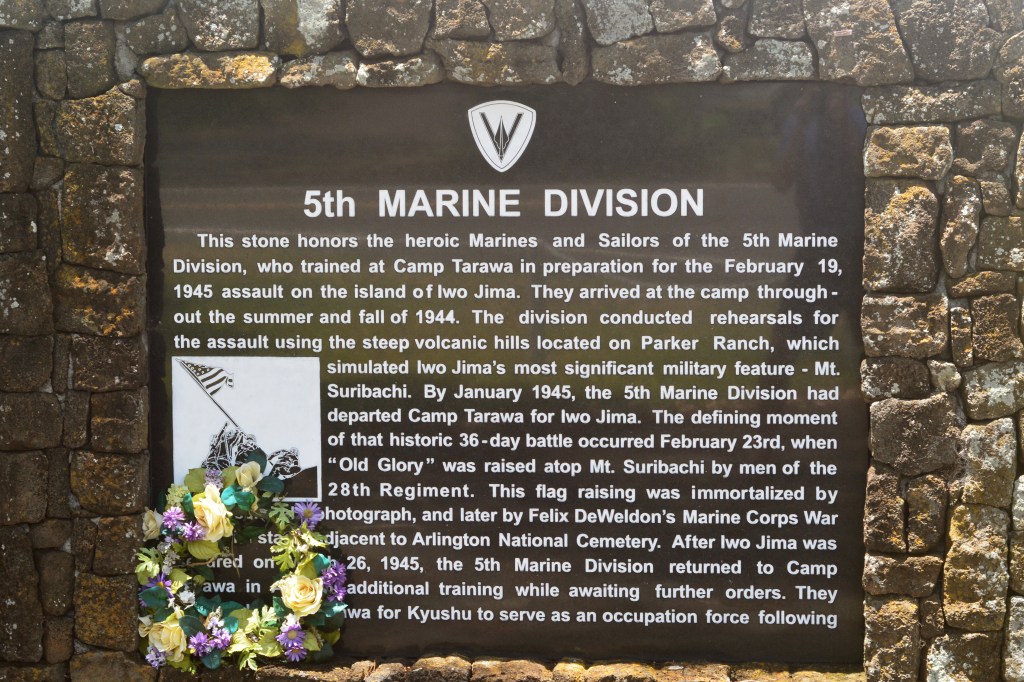

While awaiting my father’s possible return, my mother and I stayed with my grandparents at their home in Waiakea Uka, on the outskirts of Hilo, Hawaii. Early photos show me and my mother surrounded by young Caucasian men in Khaki uniforms. There was a Marine training camp just behind our home, and my grandfather provided shelter, weekend meals, transportation, mail service, pharmacy supplies and newspapers from his drug store downtown. The Marines were training for the Iwo Jima landing.

***********************************************

Harry Arthur Wessel arrived in Hilo in 1912 to work as a pharmacist for the Hilo Drug Company. He received his undergraduate degree from the University ofCalifornia Berkeley just prior to the San Francisco earthquake, and jobs in Northern California were hard to find. He married Tamar Reinhardt of Hilo in 1920. Shortly thereafter, he boughtthe drug company and erected the building that is now located on the corner of Waianuenue and Kamehameha Avenues in downtown Hilo. Harry was an intelligent hard worker who wasn’t afraid to speak his mind, and one of my favorite recollections of my grandfather was his comment when a prominent Hilo politician came through the store on a campaign walking tour.Harry shook his hand, looked him in the eye and said quietly: “I’m not voting for you, Doc, you know that.”

On the day before the Marines were scheduled to depart for the war, there was a knock on the front door of the Wessel home. A not so young Marine sergeant had a gift, a newly framed pastel painting of an island scene. The inscription on the back read as follows:

Grant Powers, Pl. Sgt. USMC, To Harry Wessel, with thanks and best wishes from the boys in the “Fifth”.

Powers, a Philadelphia native, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1921 with a degree in architecture. He joined the Philadelphia Daily News and worked there as an illustrator, cartoonist and sports writer until 1942, when he re-enlisted in the Marines. He survived the landing at Iwo Jima. Combat Team 28 had the unenviable task of taking Mt. Suribachi. Of sixty-nine sergeants, only six survived. After retiring from the Marines, Powers settled in Central Sandwich, New Hampshire, where he was a landscape artist and cartoonist. He died there in 1978.

The painting went to my mother’s younger sister after my grandfather died. Recently it was given to me, and it now occupies a place of honor on a living room wall in my home in Hawaii.

My thanks to the talented and patriotic Sergeant Powers. En route to his second war, he paused in Hawaii and shared an island vision. Thanks also to the Sandwich Historical Society of Central Sandwich, New Hampshire, for their biography of Pl. Sgt. Ulysses S. Grant Powers, USMC.